Poster delivered at the 20th Annual Conference of the Pragmatics Society of Japan. Sources below image.

Augustine. [c. 395] 2002. “On lying.” In Treatises on Various Subjects. tr. Mary Sarah Muldowney. Washington: Catholic University of America.

Barthe, Roland. [1967] 1984. “La mort de l’auteur.” In Le Bruissement de la Langue. Paris: Seuil, 61-67

Cohen, G.A. 2002. “Deeper into bullshit.” In S. Buss and L. Overton (eds.), Contours of Agency: Essays on Themes from Harry Frankfurt. MIT Press, 321-339.

Duranti, Alessandro. 1993. “Indentations, self, and responsibility: An essay in Samoan ethnopragmatics.” In J. Hill and J. Irvine (eds.), Responsibility and Evidence in Oral Discourse. Cambridge University Press, 24-47.

Frankfurt, Harry. [1986] 2005. On Bullshit. Princeton University Press.

Hill, Jane. 2000. “‘Read my article’: Ideological complexity and the overdetermination of promising in American presidential politics.” In P. Kroskrity (ed.), Regimes of Language: Ideologies, Polities, Identities. Santa Fe: School of American Research, 259-291.

Krajewski, Bruce. 1987. “Interview with John Searle.” Iowa Journal of Literary Studies 8, 1: 71-83.

“He [Michel Foucault] once said to me [Searle], ‘If I wrote as clearly as you do, people in France wouldn’t take me seriously, because they think that if they can understand everything, it must be superficial.’ And he wasn’t joking.”

Nilep, Chad. 2013. “Promising without speaking: Military realignment and political promising in Japan.” In A. Hodges (ed.), Discourses of War and Peace. Oxford University Press, 145-167.

Rosaldo, Michelle. 1982. “The things we do with words: Ilongot speech acts and speech act theory.” Language in Society 11, 2: 203-237.

Searle, John. 1969. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge University Press.

Sokal, Alan. 1996. “A physicist experiments with cultural studies.” Lingua Franca 4, 62-64.

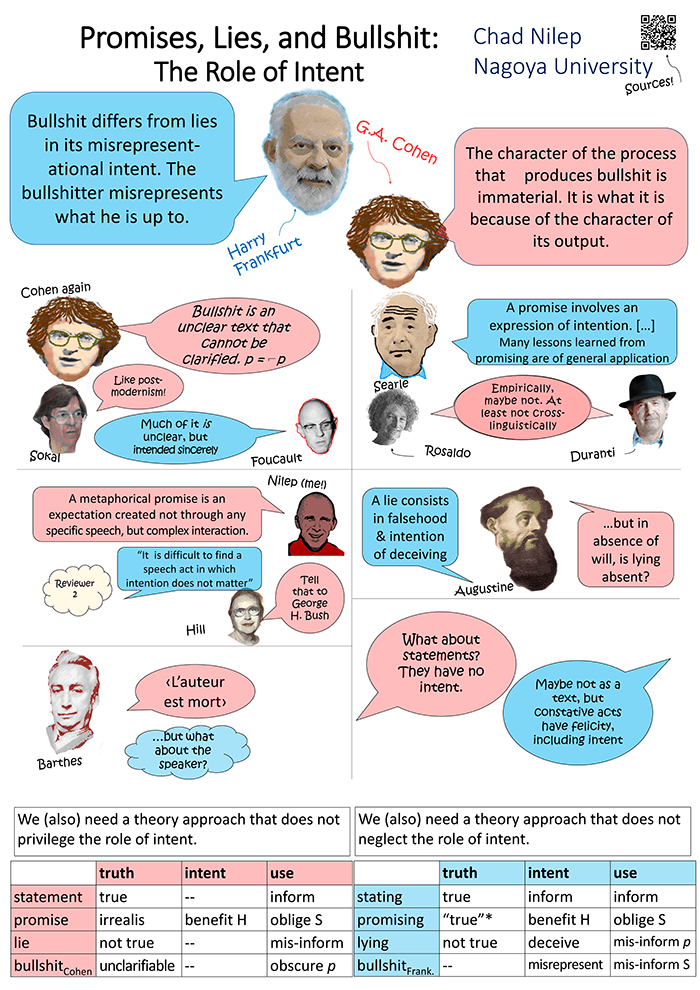

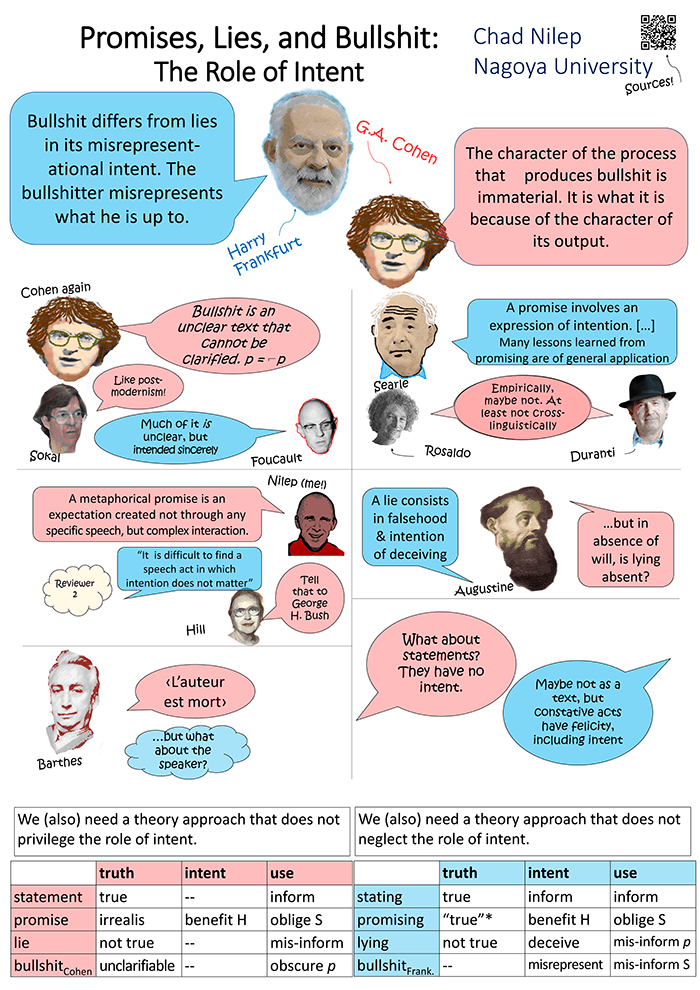

I. Introduction

This poster and explication was occasioned by a bit of a crisis surrounding my own work. I (Nilep 2013) have described metaphorical promising as a form of political speech that in some respects resembles promising as described by speech act theory (esp. Searle 1969), but that does not feature a locutionary act produced by the speaker. Separately, I (Nilep 2016) have criticized work that cites Harry Frankfurt’s (2005) writing on bullshit, but that does not share the particulars of Frankfurt’s definition. Since Frankfurt defines bullshit in terms of the speaker’s intent, I am suspicious of work that analyzes the effects of so-called “bullshit” independent from the speaker or the act of speaking. But here the conflict arises: If promising can exist without a promiser, why can’t bullshit exist without a bullshitter? If some forms of “speech” can exist without a speaker, or at least be analyzed without regard for the speaker’s intent, why is this not true for all forms of speech?

To reflect on this question, I have considered four types of discourse interaction: bullshit, as described above; lying, from which bullshit is often distinguished; promising, which Searle (1969) suggests may illustrate general qualities of speech acts; and statements of fact, which the philosophy of language often treats independently from the act of speaking, but which nonetheless can be analyzed as speech acts (Austin 1962).

This explication remains preliminary. I will not attempt to reconcile the forms of analysis I consider, nor even suggest that such reconciliation is necessarily possible. What has emerged from my thinking thus far is a belief that two different approaches to the analysis of discourse interaction are valuable and necessary. On one hand, it is useful to analyze interactions in terms of hearers and speakers, persons who have intent and knowledge. This is – very generally speaking – the kind of analysis seen in speech act theory, and in some other approaches such as stance-taking (Kockelman 2004) or some types of interactional linguistics (Selting and Couper-Kuhlen 2001). On the other hand, it is also useful to analyze various forms of language used in interaction either as texts without concern for the speaker, or at least without privileging the intent of the speaker over other elements of the language produced. This type of analysis may be seen, for example, in structuralist approaches to literature or to semiotics.

II. Explaining the excerpts

In this section I flesh out in a bit more detail the excerpts featured on the poster, and their relations to the question of speaker intent in the analysis of discourse interaction.

The poster features excerpts (in block type) and paraphrases or allusions (in script resembling hand-writing) from various scholars whose work suggests different points of view on the role of intent in discourse interaction. These philosophers, anthropologists, linguists, or critics have analyzed bullshit, promising, or lying. Some of them highlight the importance of speakers and speaker intent, while others downplay that importance. Suggestions that seem to highlight intent are shown in blue speech or thought bubbles, while those that seem to downplay it are in red.

Bullshit, and Frankfurt’s definition of it, was the initial impetus for this inquiry. Frankfurt differentiates bullshit from lying largely in terms of its relation to truth, and through what he calls the speaker’s “misreprentational intent” (2005: 16). Whereas a lie is an untrue utterance with which the speaker intends to deceive the listener, Frankfurt suggests that bullshit is uttered without regard for truth. Bullshit may be false, but it may equally be true. What the bullshitter misrepresents is not the truth of the utterance, but the nature of the interaction and the speaker’s goal. The goal of bullshit is neither to convey a true proposition nor to deceive the listener about a false one; rather, the goal is to appear to convey such propositions when in fact the speaker has no interest in their truth or falsity.

It is, of course, possible to define bullshit in other ways. G.A. Cohen (2002), in an essay responding to Frankfurt, suggests that there are two different types of bullshit, relating to two different ordinary-language meanings of the word. What Frankfurt analyzes – according to Cohen – is the action of bullshitting, talking insincerely. This corresponds to one of two definitions of the word in the Oxford English Dictionary. But the word can also refer to nonsense or rubbish, qualities of the utterance or text itself. Cohen argues that bullshit, in the sense that interests him, should be understood in terms of its own nonsensical quality, rather than by reference to the process – or the speaker – by which it is produced.

What Cohen regards as bullshit is text that conveys no sense, because it is unclear and cannot be clarified. He does not define clarity, but does suggest as a test of bullshit negating the language – that is, recasting the text in language that would express the opposite meaning. If the text is unclarifiable, both the original and its negative should appear equally (un)true, since neither expresses an actual proposition.

In his essay, Cohen refers to “academic bullshit”, which he asserts is common in post-modernist discourses that eschew truth as an attainable goal. He cites Alan Sokal’s (1996) “Transgressing the boundaries” as an example of “unclarifiable unclarity”. “Transgressing the boundaries” is an intentionally nonsensical article about the physics of gravity. It was published in Social Text, a journal of cultural studies, and then revealed by Sokal as a hoax. The affair was understood by some as an indictment of cultural studies or of postmodern philosophy, though others saw the paper’s publication simply as a failure of peer review.

Cohen’s references to postmodernism and to Sokal as examples of “academic bullshit” call to mind comments about French philosophers attributed to Michel Foucault. (Cohen also suggests that “so much of that particular kind of bullshit [i.e. unclarifiable academic bullshit] is produced in France.”) Various commenters, often citing communication with John Searle (e.g. Krajewski 1987) attribute to Foucault a suggestion that French philosophers include deliberately unclear prose in their work as a signifier of profundity. Indeed, similar charges are leveled at academics from many countries, working in many fields (e.g. Pinker 2014; Berlatsky 2016). But while work may include unclear passages, those passages are often intended to signify something – either as a proposition or as an index. Indeed, Cohen allows that “the unclarifiable may be productively suggestive,” a case which he seems to differentiate from bullshit as such.

My own work on metaphorical promising (Nilep 2013) identifies a kind of discourse that, in everyday language is called “promising” but that does not have a speaker. I show that news media use the language of possesion – e.g. “his broken promises” – to describe not only a politician’s acts of promising, but also expectations of action that are not based on the politician’s own speech. For example, the Asahi Shimbun lamented in 2009 that Yukio Hatoyama did not promise to remove US Marines from Okinawa, then in 2010 accused him of breaking that very promise.

Metaphorical promising in political discourse analysis expands on Jane Hill’s (2000) idea of political word versus message. An anonymous reviewer of my work suggested, “It is difficult to find a speech act in which intention does not matter.” That is true for analyses within speech act theory, where speaker intent is often explicitly an element of the definition of an act. It is possible, however, to analyze promises, as well as declarations, orders, or the like in terms other than those set for performative utterances. For example, Hill’s analysis of a speech by George H. Bush argues that Bush’s advisors intended it as a display of toughness, while listeners understood the text as a promise. In the end, listeners’ understandings proved important, and politician Bush was punished for breaking “his promise”, intent notwithstanding. A performative analysis would have to conclude that no promise was made, given the lack of proper felicity conditions. But an analysis from the hearer’s point of view might still treat the speech as a promise.

Analyzing discourse as text, rather than activity, resembles an approach seen in some forms of literary theory. In structuralist theory, for example (illustrated here by linguist and critic Roland Barthes), the intent and perhaps even the knowledge of the author are downplayed so that the text can be analyzed in its own right. Even within literary theory, this is only one point of view, which competes with others. Nevertheless, it suggests the possibility of approaches to discourse without concern for the thoughts of the individual who produced the words.

Much can be learned from speech act theory, but some empirical analysis finds problems with its assumptions. Searle (1969) defined promising largely in terms of the speaker’s intent. A sincere promise, Searle says, requires that the speaker intends to act, intends to take on an obligation to act, and intends to inform the hearer of this obligation. The definition of promising is highly elaborated because, Searle says, an understanding of promising reveals lessons that can be applied to performative utterances and speech acts generally.

Anthropologists, though, suggest that these insights regarding promising are not universal, and may reflect specific ideologies that philosophers who mainly speak English or other European languages take for granted. According to Michelle Rosaldo (1982), Ilongot speakers think of speaking as action, but their theories center imperatives rather than promises or statements as typical speech acts. Reading Searle’s list of speech acts from an Ilongot speaker’s point of view, she suggests, reveals its biases with regard to individual responsibility. Similarly, Alessandro Duranti (1988) analyzes Samoan political discourse rather than his own speech or intuitions. In so doing he identifies a “personalist view” underlying English speakers’ folk beliefs that privilege the role of the speaker in promising. In the Samoan system it is the interpretation of hearers rather than the intent of speakers that is centered in analyses of political speech. All of this suggests that intent need not be a privileged category in analyzing speech as action.

Like promising, lying – a form of speech that Frankfurt differentiates from bullshit – is often defined in terms of speaker intent. To count as a lie, speech must not be true. But more than that, the speaker must know that the proposition is untrue, and intend to deceive the hearer about this truth value. Augustine (c. 395) is a classic source for this distinction. But Augustine expressed less certainty about uttering falsehoods without intent to deceive, at least in moral terms. Similarly, modern philosophers debate whether uttering a statement that the speaker believes is false but that is not intended to deceive hearers may be classified as a lie (Fallis 2010).

Even statements, a form of speech classically analyzed in terms of truth value and textual form, can be analyzed in performative terms as constative speech acts (Austin 1962). Viewed as performatives, constatives have felicity conditions. Thus speaker intent could, in principle, be an element of their analysis.

Statements, lies, bullshit, and promises could each be analyzed as actions, in which case the intent of the speaker should presumably be part of the analysis. At the same time, though, it is possible to analyze any of them as texts, without privileging speaker intent above hearer’s understanding or other elements of meaning, form, or use.

III. Preliminary conclusions

By considering these four types of discourse interaction in concert – promises, bullshit, lies, and statements – we seem to reach two opposite conclusions: It is possible, and perhaps desirable, to analyze discourse as text, without much concern for the intent of the speaker or writer. At the same time, it is possible and perhaps desirable to analyze discourse as behavior, with attention to the intent of the speaker, as well as the reaction of the hearer and the result of the interaction.

Can we reconcile these opposite conclusions? Is a general theory of discourse that encompasses each of these interaction types possible? Is such a theory desirable? Is it necessary? As yet, I can offer no defensible answer to these questions, but will discuss some corollaries and a preliminary solution.

Is a theory of speaking that includes speaker intent desirable? Yes. Such a theory could help analyze and potentially account for many pragmatic facts related to such phenomena as politeness, indirectness, presupposition, and the like.

Is a theory that does not require accounting for speaker intent desirable? Yes. Such a theory could help analyze and potentially account for social facts such as intersubjectivity, historically significant “big-D” Discourses (Gee 2015), or shared ideologies, which seem to exist beyond individual speakers.

Is it possible to reconcile the “activity” approach, which considers intent, with the “text” approach, which does not require such consideration? Maybe not. At least, an analysis could always specify by fiat its standing toward text, analysis, and intent. Such an analysis will always be partial, since it neglects the opposite theory. In that case, care should be taken not to mix “text” and “activity” analyses unless actual synthesis is attempted.

On the other hand, some reconciliation may be possible. In everyday language use, speakers and hearers may orient toward their use of language as activity or as text (or as either in turns). Ethnography, situated discourse analysis, and the like may reveal to the analyst whether and how language users orient toward intent and truth in a particular event. What I have described, however, is a program toward individual analyses, rather than a clear step toward a theory that reconciles the approaches.

The two charts on the poster summarize my initial summary of a “text” approach and an “activity” approach to analysis of these four interaction types. They are reproduced here with slightly more detail.

| truth | intent | use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| statement | true | -- | inform H |

| promise | irrealis | act to benefit H inform H of obligation |

oblige S |

| lie | not true | -- | mis-inform H |

| bullshitCohen | unclarifiable* | -- | obscure P |

*Cohen-style bullshit has no clear truth value, since its proposition cannot be made clear.

| truth | intent | use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| stating | true | inform H | inform H |

| promising | “true” i.e. felicitous* |

act to benefit H inform H of obligation |

oblige S |

| lying | not true | deceive H | mis-inform H about P |

| bullshitFrankfurt | -- | meta-deception† | mis-inform H about S |

*Following Austin (1962) we might appeal to felicity in place of truth. A promise may be in some sense ‘true’ if e.g. the act promised benefits H, and ‘false’ or bad otherwise.

†Meta-deception deceives the hearer not about the truth of the proposition, but about the nature of the activity.

The approach sketched here remains preliminary. It has, however, helped to clarify the crisis that led to its undertaking. It is possible to analyze these, and presumably other types of discourse interactions either as activities or as texts. When analyzing interaction as activity, the analyst should be sensitive to speaker intent, as well as the behavior of speaker and hearer, the propositions signalled, and their relation to truth, among other factors. When analyzing interaction as text, the analyst need not privilege speaker intent over other factors, and may nonetheless produce useful analyses.

Given, however, that approaches of both types exist and have value, a particular analysis should take care to define what is being analyzed. This is especially true in work analyzing bullshit, given the less well developed literature on the topic, but is also important when analyzing other discourse activities or texts.

More sources (see also above)

Austin, J.L. 1962. How To Do Things with Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Berlatsky, Noah. 2016. “Why most academic writers will always be bad writers.” Chronicle of Higher Education, July 11.

Fallis, Don. 2010. “Lying and deception.” Philosophers’ Imprint 10, 11: 1-22.

Gee, John Paul. 2015. “Discourse, Small d, Big D.” The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction. DOI: 10.1002/9781118611463.wbielsi016

Kockelman, Paul. 2004. “Stance and subjectivity.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 14, 2: 127-150. DOI: 10.1525/jlin.2004.14.2.127

Nilep, Chad. 2016. “On bullshitology: The history of ‘women’s language’ and the future of ‘pseudo-profound bullshit’.” 9th International Gender and Language Association Conference. City University of Hong Kong, May 19-21.

Pinker, Steven. 2014. The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century. New York: Penguin.

Selting, Margret, and Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen. 2001. Studies in Interactional Linguistics. John Benjamins.

Sokal, Alan. 1996. “Transgressing the boundaries: Towards a transformative hermeneutics of quantum gravity.” Social Text 46/47: 217-252.