Archive of 'lost' blog contributions to the Society for Linguistic Anthropology

Authored by Chad Nilep. Originally published at linguisticanthropology.org.

Refreshingly careful definitions of "socialism". April 26, 2010.

The word socialism seems to be much in vogue in the United States recently, primarily as an epithet for one's political opponents, especially for representatives of the Obama Administration or the Democratic Party, but also for “the Media” collectively.

I was therefore pleasantly surprised to find two recent blog posts pointing out how this usage differs from the traditional definition of socialism as a political position. Two bloggers with quite different political positions have each taken up discussion of the word in the past week.

James Bowman, a self-described conservative writing at Cliftonchadwick's Blog, points out, “Socialism … has a particular historical meaning associated with state ownership of the means of production and distribution.” Mr. Bowman points out that the Obama Administration, which he criticizes, is not socialist. Bowman argues that Obama and other self-identified progressives seem hostile to the bourgeoisie in ways that are somewhat reminiscent of socialism, but that their actual proposals for governance are very different from those of traditional socialism.

Geoffrey Pullum is a regular blogger at Language Log. Along with his fellow blogger and co-author of Far from the Maddening Gerund, Mark Liberman, Pullum describes their output as inhabiting “neither the Trotskyite end of the spectrum nor the Mussolinian one.”

Pullum recalls the various factions of socialists in Britain during the 1970s who, he recalls, viewed everyone to their right as “to some extent fascist enemies of the people” rather than socialist fellow-travelers. In order to understand recent uses of the word, Pullum argues, “At the very least, we have to allow for a massive polysemy in the word socialist today” [hyperlink added].

I found it interesting – if all too rare – to find two writers from decidedly different positions each offering a parsing and definition of what is becoming a label of primary potency.

They are them; we are me and others. August 31, 2010

In his 30 August editorial, “We’ve Seen This Movie Before,” Stanley Fish notes that critics of Park51 (the so-called ‘Ground Zero mosque’) describe the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001 as an act committed by Islam, for which all Muslims are to some extent responsible. In contrast, the stabbing of a cab driver by an attacker who reportedly asked the driver if he is Muslim is seen as “the act of a disturbed individual,” not a representative of an anti-Islamic position.

I feel that the notion of strategic essentialism (Spivak 1988; Bucholtz 2003) may be relevant here, by an analysis through the lens of imposed adequation (Hodges 2008).

Spivak described strategic essentialism as the assumption of an identity position as a means for subalterns to organize political response while still recognizing and critiquing the problems of essentialist discourses. Hodges analyzed narratives through which American authorities equated secular Ba'athist Iraq with Qutbist Islamist al-Qaeda, imposing a politically useful identity between the two groups.

In the case Fish critiques, critics identify the builders of Park51 with the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks while denying that suspicion or antipathy toward Islam is a basis for identification.

As I say, I feel like there is an analysis there, but at this point I'll look forward to someone else making it.

Bucholtz, Mary. 2003. Sociolinguistic nostalgia and the authentication of identity. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7(3), 398-416.

Hodges, Adam. 2008. The ‘war on terror’ narrative: The (inter)textual construction and contestation of sociopolitical reality. PhD thesis. Boulder: University of Colorado.

Spivak, Gayatri. 1988. Subaltern studies: Deconstructing historiography. In R. Guha and G. Spivak (eds.) Selected Subaltern Studies. London: Oxford University Press. 3-32.

On socialism, liberalism, and neo-liberalism. February 16, 2012

Back in January “Johnson”, the language blog from The Economist, featured a post on the (mis)use of the words socialist and liberal in American political discourse.

Socialism is not “the government should provide healthcare” or “the rich should be taxed more” nor any of the other watery social-democratic positions that the American right likes to demonise by calling them “socialist”…. An awful lot of Americans have only the flimsiest grasp of what socialism is. And that, in a country that sent tens of thousands of men to die fighting socialism, is frankly an insult to those dead soldiers' memories.

Whereas socialism gets over-applied to various left-of-center positions, the meaning of liberal in contemporary US politics is almost the reverse of where it started. Johnson again:

Americans are liberal at heart…. And yet “liberal” is almost a pejorative in America, tainted as it is with associations to that demon-word, “socialist”. When people here own up to being liberals, they have to do it with a certain defiance.

I agree. As I wrote elsewhere:

The concept of liberalism, which may be defined in general terms as a political philosophy favoring individual liberty, equality, and capitalism (Hartz 1955), has a long history and deep effect on Anglo-American thought. For example, the assertion in the Declaration of Independence that all men (sic) are created equal and endowed with life and liberty by their creator echoes John Locke's suggestion that no person in a state of nature “ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions: for men being all the workmanship of one omnipotent, and infinitely wise maker” (Locke [1690] 2005:4).

Locke's version of liberalism resembles in some ways what contemporary US political discourse labels libertarianism, another term the “Johnson” post tackles.

The relationship between liberalism and small-r republicanism can also be difficult to disentangle when analyzing US political discourse. Quoting myself once more:

The challenge of defining liberal and republican is exacerbated by the fact that, in everyday political parlance in the United States, these words are used in ways nearly opposite to their definitions in the philosophical tradition sketched here. The Republican party, for example, is generally more associated with individual liberty and unfettered capitalism – that is, liberalism – than is its rival, the Democratic party. In turn, those Democrats who identify as Liberal may support constraints on private interests and the state to protect minority interests against domination, a view associated with republicanism.

(On reflection, I should add that many, though not all so-called “socially liberal” positions on civil rights, abortion, sexuality and the like are indeed liberal in Locke's sense. The fact that both political philosophers and US politicians label these positions liberal may be due to historical accident, however.)

To this list of confusing terms I would like to add one more: neo-liberalism.

Neoliberalism is a hot topic in contemporary anthropology. Anthrosource shows more than 170 papers treating the topic between 2001 and 2011. Most of these — at least, most that I have read — are excellent, insightful analyses of the ways that discourses of “freedom” and “individuality” erase structural issues in a range of contemporary settings and may exacerbate inequalities and the social problems that result from them.

As with any trending topic, however, there are inevitably a few authors who feel pressured to fit their own analyses to the currently popular discourses. My own reflections on “liberalism”, in fact, were partially inspired by suggestions that I should engage more with “neoliberalism”.

As I said, there is much excellent and necessary work being written on neoliberalism as well as globalization and late modernity. But there is also some vague hand-waving in which the terms simply seem to mean “the way things are around me” without sufficient attempt to explain what that way is like.

In my experience, one way to spot the best work is to look for authors who take pains to define these terms. This is generally true in scholarly writing, but especially so as a topic or a term becomes widely used. If “neoliberalism” is everything in contemporary societies, then it is nothing specific in an analysis. But if an analyst works to limit terms to specific (albeit sometimes nebulous) sets of practices and ideas, I generally find their work more insightful and more satisfying.

Cited references

Hartz, Louis (1955). The Liberal Tradition in America: An Interpretation of American Political Thought Since the Revolution. New York: Harcourt.

Locke, John (2005). Second Treatise of Government. Project Gutenberg.

"Ordinary" language use. April 29, 2012

In “Lesbian bar talk in Shinjuku, Tokyo” Hideko Abe analyzes linguistic behavior in twelve Tokyo bars, showing the various ways in which rezu (lesbians), onabe (‘masculine’ women), and nyuu haafu (transgendered people) construct and claim identity positions through language use. It is a solid analysis of interesting data drawn from Abe's field work and from media texts.

One passage in particular so drew my attention that I wanted to subject it to a bit more analysis. Abe interviews the manager of a lesbian bar, who she calls A. She notes that the word futsuu (ordinary) is used in complex ways, to describe both heterosexual identities and the ordinary lives of the manager and patrons of her bar.

Minna hontoo ni futsuu no renai o shite iru n desu yo ne. Naimenteki na bubun ga chigau tte yuu ka. Futokutei tasuu no hitobito ni yotte tsukuridasareta imeeji to yuu mono ga, henken o umidashita tte yuu no wa aru to omou. Shinjitsu o wakatte nai to yuu ka. Futsuu no onna no ko demo, rezu baa tte donna tokoro na no ka na, mitai na kanji de kuru shi, kite mireba, a, nan da futsuu no mono nan da mitai na. Onna no ko hitori de mo anshin shite nomi ni kite kuremasu yo. Futsuu no onna no ko mo ippai kimasu. Shufu no hito mo iru shi, kareshi ga iru kedo kuru ko mo imasu shi ne.

Lesbians have ordinary love relationships, you know. Internally, we are different. Some people created the image of lesbians as different, which created prejudice, I think. They don't know the real truth. Ordinary women come here because they're curious. Once they come, they realize how ordinary we are. Girls can feel comfortable coming here on their own to drink. Lots of ordinary women come here, including housewives and women who have boyfriends.

[Abe 2004, 210-211]

Earlier in her fieldwork Abe was surprised to hear another woman, who she calls C, use the word futsuu to mean heterosexual, “because I thought that the speaker meant that she considered herself and other lesbians not ordinary” (p. 210). In the data quoted above, though, “the speaker characterizes lesbians' love relationships as futsuu because she wants heterosexuals to be inclusive of her by thinking of her as ordinary” (p. 211). In addition to Abe's observation about two uses of the word by two different speakers, the shifting meaning of futsuu in A's speech seem to bear additional analysis.

In her description of bar patrons A uses the word futsuu four times. Twice she uses the phrase futsuu no onna no ko (普通の女の子 “ordinary girls”). This category includes shufu no hito (主婦の人 “housewives”) and kareshi ga iru ko (彼氏がいる子 “kids who have boyfriends”). Thus, like other women Abe interviewed, A uses futsuu no onna no ko to refer to heterosexual women.

Another occurrence of futsuu comes in indirect quoted speech. According to A, when they come to the bar and see what goes on women think, ‘a, nan da futsuu no mono nan da‘ (あっ、なんだ普通のものなんだ。 “Oh, how ordinary it is”).* In this example A says that newcomers to the bar—and in context this seems to include, if not refer exclusively to, heterosexual women—regard the staff and regular customers as futsuu.

The other occurrence of futsuu is translated into English as “Lesbians have ordinary love relationships”. This is a decent translation, as A appears to be talking about the patrons of her bar as well as other people who would identify as part of the same group. The Japanese sentence, “Minna hontoo ni futsuu no renai o shite iru n desu yo ne,” does not explicitly label that group as “lesbian”, however. The sentence could equally be translated as “Everybody really has ordinary romantic relationships, you know.” The key point is that minna (皆 “everyone”) can be understood as having multiple referents. While the most likely immediate reference is everyone in the bar, at the same time the word can mean lesbians generally, women generally, or all people, among other possibilities.

Abe is quite right that A's use of futsuu functions to include heterosexuals and homosexuals, bar patrons and non-patrons within a broad identity position. The multiple occurrences of the word with slightly shifting reference contribute to the effect.

* The word mono most usually refers to non-human objects or to abstract concepts. Sometimes, though, it is used for human beings. Thus the phrase could also be translated as “Oh, how ordinary they are.”

Abe, Hideko. 2004. Lesbian bar talk in Shinjuku, Tokyo. In S. Okamoto and J. Shibamoto Smith (eds.), Japanese Language, Gender, and Ideology: Cultural Models and Real People. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 205-221.

Sophmoric application of readability tests. May 21, 2012

A story on NPR's Morning Edition suggests, “the sophistication of congressional speech-making is on the decline,” citing a study by the Sunlight Foundation, a nonpartisan political organization. NPR and Sunlight both present the finding in a way that appears to validate the conventional wisdom that American politics has taken an anti-intellectual turn of late. However, both should remember to beware of intellectual bias and the danger of finding what you were looking for.

Lee Drutman, a senior fellow at Sunlight and a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University, calculated the Flesch-Kinkaid Readability score for the Congressional Record from 1996-2012. According to his calculation, text in the Congressional Record from 2005 scored 11.5, while text from 2011 scored 10.6.

According to NPR's Tamara Keith, “In other words, Congress dropped from talking like juniors to talking like sophomores.”

Nonsense. The Flesch-Kinkaid Readability Test purports to be a test of readability, not speech style. Furthermore, although the grade-level score is intended to map reading-ease scores to US grade levels, both scores need to be taken with a proverbial grain of salt.

As Gabe Doyle at Motivated Grammar argued in 2008, Flesch-Kinkaid scores do not correlate significantly with listening comprehension, even for edited prose. Transcription of extemporaneous speech is likely even less well correlated, since things like corrections, false starts, and fillers do not appear in most written texts, and there is often no obvious and uncontroversial way to segment a spoken utterance into sentences. (Flesch-Kinkaid essentially measures the number of words per sentence, and the number of syllables per word. See below for an example of how arbitrary such measurements can be.)

Of course, what lies behind Drutman's analysis and NPR and Keith's reporting of it is the impression that recent political movements, especially the Tea Party, have dumbed down the level of political discourse in the United States. New York Times columnist David Brooks has written of the Tea Party, “The members of this movement do not accept the legitimacy of scholars and intellectual authorities.” Conservative Republicans, Tea Party members, even presidential candidate Mitt Romney are accused of either being or acting dumb.

It is against this background that Drutman notes, “[The] complexity of speech in the Congressional Record has declined steadily since 2005, with the drop among Republicans slightly outpacing that for Democrats,” and NPR finds it newsworthy.

I leave it to more competent statisticians to decide whether the variation in grade level scores Drutman found is statistically significant. Given the vagaries involved in deciding how to represent speech in written form, and the irrelevance of reading ease to listening comprehension, though, I suggest that the findings are linguistically insignificant.

Just for fun — punctuation and F-K scores

Tamara Keith cites the following as an example of a sentence from the law maker with the highest grade rating, Republican California Representative Dan Lungren:

This Justice Department, in my judgment, based on the experience I've had here in this Congress, 18 years, my years as the chief legal officer of the state of California and 35 or 40 years as a practicing attorney tells me that this administration has fundamentally failed in its obligation to attempt to faithfully carry out the laws of the United States.

By my calculation, that sentence has a Flesh-Kinkaid Grade Level score of 27.63. (According to Drutman, Lungren has a “Career grade level” of 16.01.)

But the phrase “This justice department” does not appear to have a clear grammatical role in any of the clauses that follow it. “This justice department” looks like a topic initiation, and it is co-referential with “this administration”, the subject of an embedded clause. But it is not an argument in the clauses “my years… tells me” [sic] or “this administration has fundamentally failed”, nor in the non-finite clause “obligation to attempt to faithfully carry out the laws”, and it's certainly not an argument of “I’ve had here”.

Likewise, the phrases “the experience”, “18 years”, and “my years” all appear to refer to the same thing. Lungren thus re-starts the utterance several times. Such restarts are not uncommon in extemporaneous speech.

What if we change the punctuation to make the abandoned and re-started topics in Lungren's utterance free-standing sentence fragments?

This Justice Department. In my judgment, based on the experience I've had here in this Congress. 18 years. My years as the chief legal officer of the state of California and 35 or 40 years as a practicing attorney tells me that this administration has fundamentally failed in its obligation to attempt to faithfully carry out the laws of the United States.

Suddenly grade level drops to 9.68. Is this a more sensible way of calculating grade level? Probably not. Both transcriptions make somewhat arbitrary choices to force the extemporaneous speech into something resembling written prose. Neither tells us anything particularly interesting about Representative Lungren or his speech style. Any analysis of either should probably remain where Drutman says the idea came from: “We just kind of did it for fun.”

Afterword

I anticipate that some commenter may refer to Wisconsin Republican Governor Scott Walker's position on public education, or erstwhile presidential candidates Rick Perry, who promised to eliminate the US Department of Education, or Rick Santorum, who seemed to suggest that college attendance is snobbery, as evidence of an anti-intellectual bent among Republicans. I'll stake no strong position on such an argument at this time, but will assert that simple-minded word counting is a poor gauge of trends in political ideology under the best of circumstances.

I also recommend Mark Liberman's 2010 critique on Language Log of a conversely simple-minded conclusion, a suggestion that a speech by President Obama was “too professorial”. Amusingly, in 2010 Obama's ninth-grade reading level speech was called too complex, while Congress's average tenth-grade reading level speeches are now called unsophisticated.

Can analysis of discrimination help overcome fear? June 4, 2012

[The following is a personal reflection by Chad Nilep. It does not reflect the views of Akiyo Cantrell, the SLA, or any other person or group.]

One morning, about a month after the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake, I was reading the newspaper while eating my breakfast. At the time more than 12,000 people were dead or missing as a result of the tsunami that the earthquake had caused. In addition, hydrogen gas explosions had damaged or destroyed buildings at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, and it was widely suspected that reactors at the plant had suffered meltdown. The steady flow of bad news from the Tohoku area, where the earthquake and tsunami were centered, was saddening, but I felt little actual fear since my home is more than 400 km (250 miles) from the worst-affected areas.

A story on the front page of that day's newspaper described various hardships that evacuees from Tohoku were facing. These hardships were not directly related to the loss of their homes and loved ones, nor directly caused by the earthquake, tsunami, or nuclear disaster. Rather, the story detailed how evacuees were being ostracized by people's vague fears of Tohoku, and especially Fukushima. School children were bullied, companies lost business, and municipal landfills received protests from people who feared that “Fukushima” represented something unwholesome and dangerous.

I was immediately reminded of the hibakusha “bombed people”, the survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. Like the Fukushima evacuees described in the newspaper article, survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were harmed once by the bombing and then again by discrimination stemming from people's fears that association with the bombing made them somehow untouchable.

My colleague, Akiyo Maruyama Cantrell, had written an outstanding dissertation about survivors in Hiroshima, and how their work at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum contributes to collective memorialization of the bombing and its after-effects (Cantrell 2006). It seems that Akiyo, too, was noticing a parallel between these rumors; she also noted comments from hibakusha in Hiroshima worried about the possible effects of fear.

Akiyo and I produced a paper comparing news coverage of evacuees' experiences in 2011 with survivors' stories from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (Cantrell and Nilep 2012). In it, we suggest that ignorance and fear can compound the suffering of disaster victims, and we hope that more reasoned understandings can spare victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake from discrimination like that seen after World War II.

Sadly, I see continuing distrust in recent news coverage about tsunami flotsam arriving in North America and the reluctance of Japanese communities to help dispose of tsunami debris. I cannot really call distrust of government or industry assurances irrational, given that government reports have been confusing and corporate announcements may be self-serving. But I do hope that people in Japan and around the world can overcome their fear and suspicion in order to embrace survivors from Fukushima, Iwate, Miyagi, and other areas affected by the disasters.

I don't know how much academic papers or personal blog postings can contribute to Japan's recovery, but I sincerely hope that we are helping to move in the right direction.

Cantrell, Akiyo Maruyama. 2006. Hiroshima Stories: The Construction of Collective Memorialization in Survivors' Narratives. PhD Dissertation. Department of Linguistics, University of California, Santa Barbara. AAT 3238784.

Cantrell, Akiyo, and Chad Nilep. 2012. “You are contagious”: When talk of radiation fears overwrites the truth. NU Ideas 1(1), 10-14.

Another possible definition of "socialist". June 18, 2012

Yesterday I was listening to Jane Mayer, a writer for The New Yorker, being interviewed by Terry Gross. Mayer has recently written about Bryan Fischer, a conservative religious radio talk-show host. Mayer attributed an idea to Fischer and others in what she calls “the farthest edge of the Evangelical Christian right”.

I think everything you need to know about how they see Obama was what happened at um where Bryan Fischer works with the American Family Association. Shortly after the election in 2008 the group that calls itself a Christian ministry passed around a picture of Obama’s face which they had blended with that of Adolf Hitler. And they sort of posted it on the wall and they passed it around and all laughed at it and you know it showed Obama with you know a little Hitler mustache and swastikas behind him. But they have attacked Obama relentlessly since his election in 2008. And um they regard him as sort of the avatar of godless socialism, so an assault on everything they think they believe in.

[Note: My transcription of the radio broadcast differs slightly from NPR's.]

What struck me is Mayer's use of the word socialism, and particularly the phrase godless socialism. I have written previously about the word socialism and other labels for political philosophies, and how the popular use of such terms differs from their use in political science and other scholarly fields.

The phrase godless socialism and its opposition to Evangelical Christianity seems to suggest a religious, rather than an economic position. One definition of socialism (or Socialism) is “a theory or system of social organization based on state or collective ownership and regulation of the means of production, distribution, and exchange for the common benefit of all members of society” (Oxford English Dictionary 2012). But the idea of godless socialism as described by Mayer seems relatively unconcerned with means of production or economic regulation, and instead to concern the place of God and religion in social organization.

The phrase godless communists was fairly common during the Cold War, an idea I assume relates to the atheist and sometimes anti-religious nature of the Soviet and the Chinese communist parties, as well as Karl Marx's argument that religion is “the opium of the people”. In retrospect, it makes perfect sense that an opposition between communism (and by extension socialism) versus religion should become salient to religious people, particularly those opposed to communism on economic, nationalist, or other political bases.

It is Mayers, the critical reporter, and not Fischer, the Evangelical Christian and political opinion speaker, who used that term. Therefore, I don't know whether this usage is common among politically conservative Christians, or even whether the word is used this way.

If it is common, though, I find that very interesting. It is not that I am unfamiliar with such usage of socialism, but rather that I am familiar with the usage from a quarter that, I suspect, the Evangelical Christian right would strongly reject.

Consider the following message from Osama bin Laden, as broadcast on al Jazeera 11 February 2003 and translated by BBC Monitor.

Under these circumstances, there will be no harm if the interests of Muslims converge with the interests of the socialists in the fight against the crusaders, despite our belief in the infidelity of socialists.

The jurisdiction of the socialists and those rulers has fallen a long time ago.

Socialists are infidels wherever they are, whether they are in Baghdad or Aden.

Here “the socialists” refers to Iraq under Saddam Hussein, while “the crusaders” refers to the United States under George W. Bush. Bin Laden labeled Hussein a socialist based not [primarily] on economic philosophy but on his secular approach to governing and his (in bin Laden's view) insufficient religious piety.

“socialism, n.”. Oxford English Dictionary online. June 2012. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/183741.

Where have all the numbers gone? (or 1+99=53+47). December 5, 2012.

At least one commentator has noted that 2011's numerical “word of the year”, 99%, seems to have disappeared in 2012.* In its place 2012 saw a similarly politically-charge percentage, 47%. Those numbers, it turns out, are rather more closely related than might be immediately apparent.

December and early January are traditionally a time for looking back on the past year. Media and interest groups frequently compile “top ten” or “best of” lists, noting events during the past year that were particularly interesting to them. For language lovers, this includes various Word of the Year nominations, such as the American Dialect Society's WOTY selection during its annual meeting each January.

American Dialect Society Executive Secretary and Chronicle of Higher Education blogger Allan Metcalf recently noted how the trendy words of yesteryear tend to fade quickly. At the Lingua Franca blog Metcalf noted, “In 2011 we were preoccupied with ‘occupy,’ with a new specific meaning derived from the Occupy Wall Street movement and its progeny across the nation and around the world.” ADS's 2011 Word of the Year was occupy, and related words such as people's mic and the 99 percent were noted in a special Occupy Words category. What is the fate the 99 percent a year later, Metcalf wonders. “That’s so 2011. This year it’s the 47 percent.”

As people who followed the 2012 presidential campaign will recall, 47% became a politically charged number thanks to a video of a Mitt Romney fundraiser released by Mother Jones magazine. In the surreptitiously recorded segment Romney declares,

There are 47 percent of the people who will vote for the president no matter what. All right, there are 47 percent who are with him, who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe that government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you name it. That that's an entitlement.

(Worth recalling in this context are Geoff Nunberg's comments on the Janus-headed meaning of entitlement.)

Critics seized on Romney's impolitic remarks, making 47% a politically loaded number, emblematic of Romney's inability to relate to working class and lower-middle class people.

From 99% to 47%

Where does the number 47% come from? According to Romney's remarks, “Forty-seven percent of Americans pay no income tax. So our message of low taxes doesn't connect.”

(As various commentators pointed out at the time, American adults who pay no income tax include retirees and people who do not work because they are disabled or are in college, or are out of work for other reasons. In addition, some working Americans owe no federal income tax because they earn too little money, though such workers pay other taxes, including federal payroll taxes.)

The idea that 47% of Americans pay no income tax finds its complement, in arithmetic as well as discourse terms, in the declaration that 53% of Americans are hard working tax payers. And that declaration arose as a response from the political right to Occupy Wall Street.

One of Occupy Wall Street's popular slogans is “We are the 99%”. This slogan, sometimes attributed to anthropologist David Graeber, is meant to evoke broad inequality in the US economy. One percent of the US population earns about 24% of the nation's income, leading not only to poverty at the lowest income levels but also to wide disparities between the middle- and upper-classes.

A popular means for Occupy Wall Street supporters to spread their message was** by posting photographs of themselves at wearethe99percent.tumblr.com and other social media outlets. In the photographs activists typically hold up sheets of paper describing financial or social hardships they face, such as lack of access to health care or inability to find jobs or satisfactory housing. These notes usually end with the phrase “I am the 99%.”

In response to the 99 percent, conservative bloggers and other activists launched the53.tumblr.com. Like wearethe99percent, the53 featured photographs of activists holding up sheets of paper describing their hard work, sometimes at multiple jobs, to earn a living. These testimonies frequently criticized the 99 percent as lacking initiative or whining about their lot. The notes usually end with the phrase “I am the 53%.”

It is cannot be known whether Mitt Romney's 47% statistic was taken directly from the53.tumblr.com, but both are part of the same circulating discourse. Economists differ somewhat on the precise number of Americans who pay income taxes, but Romney and the53 each offer the same figure.¤ Whether or not the Mitt Romney campaign and the curators of the53.tumblr.com communicated with one another directly, they participated in the same discursive formation.

As I argued at the recent American Anthropological Association meeting,

Political speech is always polyphonic. Politics, by definition, involves multiple individuals interacting and communicating with one another. The communicative practices that comprise political action – discussion, persuasion, authorization, dissent, among others – are intimately tied to the thoughts and to the words of other people. Even the most personalist of speech acts […] does not happen in isolation.

*Perhaps the term seems to have disappeared in relative terms, though it still occurs, as do related terms, particularly in publications that are sympathetic to the political left.

**One could say that this is a popular way of demonstrating. The most recent addition to wearethe99percent.tumblr.com came one month ago, 6 November 2012.

¤In his recorded remarks, Mitt Romney did express some numerical indecision, but was firm on the percentage of non-tax-payers. He suggested, “And I mean, the president starts off with 48, 49, 48—he starts off with a huge number. These are people who pay no income tax. Forty-seven percent of Americans pay no income tax.”

Arana: Good sociolinguistic conclusion despite questionable examples. January 16, 2013

Gabriel Arana, web editor of The American Prospect, recently published a defense of creaky voice at The Atlantic. Arana notes that recent criticism of young women's use of creaky voice, or “vocal fry”, is part of a long tradition of critiquing the speaking styles of less powerful groups of people. Arana's conclusion that “normative judgments about linguistic prestige are relative, and merely reflect social attitudes” is absolutely correct and well-known to linguistic anthropologists and other scholars of language. The particular speech patterns he analyses to support his conclusion, however, are somewhat questionable.

Arana suggests that like creaky voice, up-talk (rising intonation in declarative sentences) and the discourse marker like are innovations attributable to young, urban women. Certainly, each of these non-standard forms is frequently attributed to young women. Furthermore, empirical studies do suggest that women are often more innovative than men in terms of language change (e.g. Fasold 1968; Labov 1972; Nichols 1978; Gal 1978; inter alia) and that the speech of young women is frequently stigmatized. But the sociolinguistic and historical data on up-talk, like, and creak provides a far less clear picture.

I am less familiar with the literature on up-talk, but can point to the ever-insightful Language Log for meta-analysis of work on the phenomenon. Mark Liberman reviews work in which the rising intonation is found among high-status individuals (men as well as women) and others where it is associated with low status and especially with young women. (More Language Log posts on uptalk can be found here.)

I am more familiar with work on discourse markers and creaky voice. The use of like as a discourse marker has a fairly long history. As Jim Miller and Regina Weinert (1995) point out, the usage has appeared in fiction since the nineteenth century, and is likely much older in speech.

Sali Tagliamonte's 2005 study of discourse markers used by Canadian teens found that like was more common among young women than young men. But Tagilamonte's work also suggested that this is not a linguistic change in progress, but age-graded variation.

Sociolinguistic variation associated with young people can have two causes. A “change in progress” occurs when a new form is entering the language. Such change is noticeable in the differences between the speech of young people and that of older people who maintain the older form. This is the kind of “linguistic unorthodoxy” That Gabriel Arana celebrates in young American women's speech. But another kind of variation, age grading, does not reflect a changing language. Some forms of language are used by people of a particular age but then abandoned later in life. A classic example is Canadian children who call the last letter of the Latin alphabet /zi:/ in contrast with Canadian adults who call it /zεd/. This variant pronunciation has been seen for decades among fans of Sesame Street and similar US television programs, but has not resulted in a change among Canadian adults. At some point, it appears, young Canadians switch to /zεd/ and follow the adult pattern.

Tagliamonte found that 15 and 16 year olds in Toronto used the discourse marker like more frequently than those aged 17 to 19, but also more than those younger than 15. This is the sort of pattern we would expect to see with age grading. While Tagliamonte's corpus was too small to be the basis of definitive claims (just 26 speakers), it gives us reason to question the idea that youth are leading a vanguard of like as a discourse marker.

So-called “vocal fry”, also known as creaky voice or laryngealization, has received a good deal of attention from amateur as well as professional linguists over the past year or so. Between December 2011 and February 2012 the phenomenon was noted in sources from Science Now to MSNBC and the New York Times.

In Februay 2012 New York Times reporter Douglas Quenqua cited a then-unpublished paper (it has since come out in the May 2012 issue of the Journal of Voice) by Lesley Wolk, Nassima B. Abdelli-Beruh, and Dianne Slavin describing the acoustic characteristics of vocal fry in the speech of 34 female American college students.* He also spoke to Abdelli-Beruh and to Penny Eckert, both of whom suggested that phonation can express meaning; and to Carmen Fought and Language Log's Mark Liberman, who both noted that linguistic innovation tends to be evaluated negatively. Like other news reporters and bloggers, Quenqua suggested that vocal fry was a new fad among American women.

Faddish it may be, but creaky voice is hardly new. As Liberman noted in 2011, Wolk, Abdelli-Beruh, and Slavin did not trace changes over time (nor did they compare women and men). Liberman also cites work in phonetics since the 1980s finding that creaky voice is not uncommon in American English, especially at the ends of phrases.

My own work with Tamara Grivic in 2004 found that American English speakers (all men in our small study) use the word yeah with creaky voice to essentially give up a turn to talk. We also cited earlier work such as Ben Blount and Elise Padgug (1976) who found creaky voice in American parents' child-directed speech, and Jeffrey Pittam (1987) who found it among Australians. In both of those studies, the phenomenon was somewhat more common among men than women. John Laver (1980) also described creak among British speakers of Received Pronunciation.

Gabriel Arana is correct in his conclusion: people who revile young women's creaky voices reveal more about their attitudes toward young women than their sensitivities to acoustic correlates. But his examples of linguistic innovation are not quite as clear as he makes them out to be.

References

Blount, Ben and Elise Padgug. 1976. Mother and father speech: Distribution of parental speech features in English and Spanish. Papers and Reports on Child Language Development 12: 47-59.

Fasold, Ralph. 1968. A sociolinguistic study of the pronunciation of three vowels in Detroit speech. Washington, D.C.: Center for Applied Linguistics. (manuscript)

Gal, Susan. 1978. Peasant men can't get wives: Language change and sex roles in a bilingual community. Language and Society 7:1-16.

Grivicic, Tamara, and Chad Nilep. 2004. When phonation matters: The use of yeah and creaky voice. Colorado Research in Linguistics 17(1).

Labov, William. 1972. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Laver, John. 1980. The Phonetic Description of Voice Quality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, Jim, and Regina Weinert. 1995. The function of LIKE in dialogue. Journal of Pragmatics 23: 365-393.

Nichols, Patricia. 1978. Black women in the rural South: Conservative and innovative. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 17: 45-54.

Pittman, Jeffrey. 1987. Listeners' evaluations of voice quality in Australian English speakers. Language and Speech 30(2): 99-113.

Tagliamonte, Sali. 2005. So who? Like how? Just what? Discourse markers in the conversations of young Canadians. Journal of Pragmatics 37: 1896-1915.

* It is curious to me that, while the Wolk, Abdelli-Beruh, and Slavin paper was widely cited, a 2010 paper by Ikuko Patricia Yuasa in American Speech did not receive much attention. Unlike Wolk and her colleagues, Yuasa actually did find creaky voice to be more prominent among American women than among American men or Japanese women.

Evolution and 'lies to children'. October 7, 2013.

We – we anthropologists, we scholars, we folk who act like we know what we're talking about – tend to talk about complicated phenomena in ways that simplify them. This is necessary in teaching, in public outreach, and even in presenting work to our colleagues. We need to first make ourselves understood and then to try to come ever closer in our approximation to the real complexity of an idea or phenomenon. These technically untrue approximations of complex truths are sometimes called “lies to children”.*

Talk about evolution tends to be replete with metaphors about natural selection. We talk about the “goals” of evolution or the “choices” that species or individual genes make, even if we don't believe that there is any intelligence at work in the process. Even talk about the “reasons” for a particular evolutionary outcome are usually imprecise approximations.

I was thinking about all of this after listening to a recent Fresh Air radio broadcast. Terry Gross interviewed Daniel Lieberman, Harvard professor of human evolutionary biology, about his recent book, The Story of the Human Body.

Now I hate to complain about this. I am pleased when news media interview scientists directly rather than relying on journalists or publicists to explain scientific work, and Fresh Air works hard to get excellent interview subjects. But while listening to the interview I was deeply uncomfortable about the ways Gross and Lieberman talked about evolution. It was really more of a feeling than a well-formed idea at the time, so I went back later and listened again to the podcast of the interview to try to understand what made me so uncomfortable.

I'm still thinking about the question of what made me feel that there was something misleading in the description of evolution, but this is a first approximation.

Lieberman and Gross discussed how changes in human diet and lifestyle lead to “mismatch diseases”, non-infectious, lifestyle-related illness. I've transcribed part of the interview to illustrate two issues.

Terry Gross: Why are our bodies ill-equipped for the kinds of foods and fats and sugars, and the quantity of food that we're eating now?

Daniel Lieberman: Yeah well this is an important topic, obviously. You know, in India and China for example rates of diabetes are going up by almost an order of magnitude over the last generation, and they're going up very rapidly in the US, too. And the reason they're mismatch diseases is that diabetes, for example, is caused by essentially the body being unable to cope with sugar in the bloodstream. So, we evolved to crave sugar because sugar is an energy-rich food, but we didn't evolve to digest large amounts of it rapidly.

Gross: So our bodies, the basic operating system of our bodies was designed for the hunter-gatherer era, right?

Lieberman: To a large extent. I mean hunter-gatherers, and even before hunter-gatherers, chimpanzees for example, eat plenty of foods that have carbohydrates. For example chimpanzees eat almost all fruit, right. … [But] Most wild fruits are only about as sweet as a carrot. So we love sweetness, but until recently pretty much the only food that we got that was very sweet was honey, and honey of course was a special treat. That was pretty much the only form of dessert in the paleolithic.

(The bit I've left out, marked by the ellipsis and bracketed [But], is Lieberman's description of the sugars in fruit.)

There are two problems I see here. One problem is that Gross's second question and it's evocation of “the hunter-gatherer era” seems to suggest a view of evolution more in tune with Herbert Spencer than Charles Darwin, let alone contemporary evolutionary biology or anthropology. For Spencer and some other nineteenth century thinkers, evolution was thought to have a goal, a specific end-point. In biology, the “survival of the fittest” (Spencer coined the phrase) ensured that “higher” species would survive while “lower” ones eventually failed to reproduce. In human societies, hunting and gathering would give way to agriculture, and eventually to industrial “civilization”. Such theories were the the cause of, shall we say, considerable problems with early anthropology.

Now I have no reason to believe that Lieberman or Gross subscribe to such notions of evolutionism or social Darwinism. But the presupposition that there was, and no longer is, a “hunter-gather era”, and the failure to note the presupposition as problematic, may have contributed to my discomfort.

A second problem I see in this excerpt is its treatment of time. According to Lieberman, the mismatch he is describing has developed “over the last generation”, but also since “the paleolithic”. (No matter what my nieces may think, we were not actually living in the Stone Age a generation ago.) There is even a suggestion, in the discussion of chimpanzees “even before hunter-gatherers” that this mismatch developed around the time that the Homo and Pan genera diverged. So the problem of mismatch diseases is approximately 20 or 15,000 or 2.5 million years old. That's a pretty rough estimate.

Now as I said, this kind of rough, even technically false approximation is a necessary step in explaining complex phenomena, and I shouldn't criticize anyone too strongly for failing to get into all the messy complexity of advanced scholarship in a half-hour radio broadcast. Nevertheless, it makes me uncomfortable.

Lieberman's answer to Gross's last question suggests that he is able to explain things in a way that even I will not find discomforting.

Gross: Have we stopped evolving?

Lieberman: Definitely not. Evolution is always churning along. Evolution, after all, is just change over time, and natural selection, which is the kind of evolution we tend to be thinking about the most, is caused by just a few phenomena that are always there. … [But] what’s a more dominant form of evolution today is cultural evolution. It’s how we learn and use our bodies and interact with each other based on learned information. And that’s also a kind of evolution. It’s not Darwinian evolution, it’s not biological evolution, but it affects our bodies. We’re evolving slowly through natural selection and rapidly through cultural evolution.

This, I fancy, captures Lieberman's point nicely. Biological change through natural selection is slow, while cultural and technological change is fast. This suggests one possible treatment for my current discomfort. I'll need to go out and read Lieberman's book.

*Wikipedia says that the label “lies-to-children” is due to science fiction author Terry Pratchett. Who knew?

Shock. Lehman schock. November 25, 2014

I am somewhat puzzled by a label I commonly hear in Japanese news media. In reports on economy and trade, news announcers and pundits frequently discuss the “Lehman shock” (リーマン・ショック), sometimes short-handed as “Lehman”. The etymology of the term is entirely clear: it is an allusion to the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the investment bank whose 2008 bankruptcy and liquidation is seen as symbolic of a wider financial collapse. What puzzles me is how, at least in Japan, that bank's collapse seems to have become so widely used as shorthand for what is variously called the Global Financial Crisis or the 2008 collapse, and attendant shocks sometimes called the Great Recession.

For quite some time I have had the impression that “Lehman shock” is a commonly used phrase in Japanese media. To check that subjective impression, I searched the archives of the Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, and Tokyo Shimbun for headlines containing the word “リーマン” in reference to the so-called Lehman shock or associated events. Unfortunately, I couldn't access the archives of Japan's largest daily newspaper, Yomiuri Shimbun, nor financial papers such as Nihon Keizai. Nonetheless, the numbers show that the label is still in common use.

|

2008

(Sep-Dec) |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014

(Jan-Oct) |

| Asahi |

4 |

17 |

20 |

21 |

24 |

44 |

23 |

| Mainichi |

7 |

10 |

6 |

9 |

9 |

16 |

6 |

| Tokyo |

2 |

15 |

13 |

10 |

0 |

25 |

8 |

| Occurrences of リーマン (Lehman) in newspaper headlines |

(These numbers should be taken with requisite grains of salt. Although I did my best to eliminate false-positives, such as occurrence of the string within the word サラリーマン (salary-man), and to include only references to the financial crisis, I can't say with certainty that I didn't make any errors of that kind, or other errors I didn't think to check for.)

The chart suggests that use of リーマン has not declined significantly. By contrast, 金融危機 (“financial crisis”), a phrase used in literally hundreds of headlines in late 2008, has fallen off precipitously. These numbers are for Asahi only; I didn't check the other two papers.

|

2008

(Sep-Dec) |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014

(Jan-Oct) |

| Asahi |

301 |

103 |

30 |

5 |

8 |

4 |

5 |

| Occurrences of 金融危機 (financial crisis) in Asahi Shimbun headlines |

To be sure, the collapse of Lehman Brothers was a big deal, and it seemed to strike many people as an emblem of financial uncertainty around the subprime mortgage crisis and related (especially following) crises. There was, for example, a BBC film about The Last Days of Lehman Brothers.

But Lehman was neither the first nor the largest institution to fall. BNP Paribas is noted as the first bank to recognize the crisis when it froze withdrawals in August 2007; it emerged from the crisis largely unscathed. Bear Stearns, on the other hand, only narrowly avoided bankruptcy by selling its assets in March 2008; Countrywide was sold to Bank of America in July amid rumors it was essentially bankrupt; and U.S. mortgage traders Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac entered “conservatorship” in September, a week before Lehman filed for bankruptcy.

Even more curious: some of the financial contraction referred to under the リーマン・ショック heading seem to pre-date not only the fall of Lehman Brothers, but the whole 2007-08 crisis. A rising poverty rate in Japan, sometimes blamed on リーマン・ショック, was already on the way up by 2006. And while it is frequently noted that Japan has suffered four recessions since 2008, it also suffered recessions in 2001 and 1998, as well as periods of negative growth in 1999, 2003, and 2007 following the bursting of its bubble economy.

Perhaps this could be explained with reference to Arnold Zwicky's reminder that labels are not definitions. I do wonder, though, about journalistic labels that suggest false definitions.

Grammar in the news. July 7, 2015

According to an article by Reiji Yoshida in the Japan Times, word choice played an important role in an agreement to list several Japanese industrial sites as UNESCO World Cultural Heritage.

Japan has won UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Status for 23 industrial sites after conceding to South Korea’s demand that the registration make clear that some of the locations used forced laborers from the Korean Peninsula.

But in their official remarks and statements, Japanese officials avoided using the phrase kyosei rodo (forced labor), and instead used hatarakasareta (were forced to work), which is a more colloquial Japanese expression.

Yoshida calls hatarakasareta “more colloquial” than kyosei rodo, and indeed it is. Part of that colloquial sense comes from the part of speech. The word 働かされた (hatarakasareta “was caused to work”) is a verb – the past tense of the causative-passive form of the verb 働く hataraku “to labor; to work” – while 強制労働 (kyouseiroudou “coerced labor”) is a noun. Written Japanese, particularly formal writing, typically uses more nouns than spoken Japanese does. Nouns, especially those constructed from Chinese loan words, often sound more formal than verbs or adjectives describing the same phenomena.

Some background is important here. For the past several months Japanese officials have been preparing a bid to have 23 factories built during the late 19th century listed as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage property. The sites, known collectively as “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” are intended to highlight Japan's rapid modernization in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth century. South Korean officials, meanwhile, objected to the listing of these sites because seven of them employed forced labor from the Korean peninsula during the colonial period from 1910 to 1945. A few weeks ago the foreign ministers of Japan and South Korea met and reached an agreement to support one another's applications for UNESCO listing. (Eight historical sites in South Korea have also been added to the World Cultural Heritage list.)

The wording of Japan's proposal seems to allow both Korean and Japanese politicians to claim victory in the negotiations.

Japan's application materials were accepted by the World Heritage Committee at a July 5th meeting in Bonn, Germany. As Yoshida of the Japan Times points out, the UNESCO diplomats probably read the English version of the application, while the Japanese-language version was read mainly in Japan.

Japan's Foreign Minister, Fumio Kishida, told reporters that forced to work “does not mean kyosei rodo” (as quoted in Sankei Shimbun, 「『強制労働』を意味するものでない」).

But to paraphrase Bill Clinton, it depends on what “mean” means. The referent of both expressions is the same: the work done by a person who is caused to labor. But because the register and the part of speech differ one might reasonably say that the sense is not the same.

(Socio-)phonetics in the news. July 9, 2015

The relationship between linguistic anthropologists and speech pathologists is a curious one. We work with some of the same materials and issues: speech sounds, speaking bodies, language variation, perceptions of speaking styles. Yet there is a difference underlying our approaches. Individuals typically work with a speech pathologist when they or someone close to them perceives their way of speaking as a problem, so that excessive divergence from a norm is seen as pathological. Linguists working from an anthropological perspective, though, tend to view variation in more relativistic terms. Linguistic anthropologists, therefore, are less likely to see divergence as pathology, and less likely to see communication problems as necessarily failures of speech alone.

I've just finished listening to Terry Gross interview film maker David Thorpe and speech pathologist Susan Sankin on the Fresh Air radio program. (I really do enjoy Fresh Air, notwithstanding my past criticisms.) Thorpe's documentary, Do I Sound Gay?, explores what it means to “sound gay” and why he and other people react as they do to gay voices, including Thorpe's own. It sounds like an interesting film and I look forward to seeing it.

In the latter portion of the interview, however, Gross and Sankin discussed a number of speech “problems”, and it is here where I have a problem with the discussion.

In an early part of the interview, Sankin describes “uptalk” as her “pet peeve”.

I think perhaps that's coming from the trend to embrace up-speak? one of my pet peeves.

[...]

that tendency to kind of speak in that, in that way where you're going up? makes your voice sound a little bit more musical?

and I think that's what people associate with a gay sound to some degree.

We all have our pet peeves – I'm not a fan of impactful or other words that I think of as business neologisms – so I'm certainly in no position to criticize Sankin's personal taste. But in the later part of the interview, Sankin suggests some things about “up-speak” that I find more problematic. One minor point is Sankin's suggestion that it is a recent innovation among young women.

Terry Gross: OK, so when did you start hearing up-speak, and when did you start hearing it become widespread?

Susan Sankin: It's been around for awhile. I would say at least the last couple of years, but maybe longer than that. Initially when I heard it, it was among younger women. um It seems now though that men have caught on as well. And it's become as contagious as the common cold.

This use of rising intonation has indeed been around for longer than a couple of years. In her 1975 book Language and Woman's Place, for example, Robin Lakoff includes this.

There is a peculiar sentence intonation pattern, found in English as far as I know only among women, which has the form of a declarative answer to a question, and is used as such, but has the rising inflection typical of a yes-no question, as well as being especially hesitant. The effect is as though one were seeking confirmation, though at the same time the speaker may be the only one who has the requisite information.

(13) (a) When will dinner be ready?

(b) Oh… around six o'clock…?

[Lakoff 1975]

Like Sankin, Lakoff attributes the usage to women, and sees it as undercutting women's authority. Even in 1975, however, there is reason to believe that – contra Lakoff's assertion – the pattern was not unique to women. According to the 2004 revised edition of Lakoff's book, “This phenomenon has recently been recognized in the popular press, associated with adolescent speech, under the name ‘uptalk’.” I believe that noted up-talker George W. Bush would have been 29 in 1975; I wonder if that counts as adolescent?

There is another minor point I can't resist raising. You might note that I've included three question marks in the transcription of Sankin's speech above, marking what I hear as rising intonation. I'm not a phonetician, and perhaps someone will correct me in the comments below, but I hear those as ‘uptalk’ or ‘up-speak’. The pitch at each of those places rises noticeably, from 150Hz to 216Hz on up-speak and from 149Hz to 333Hz on going up, and from 146Hz to 260Hz on musical. This is not the same rising terminal intonation described by Robin Lakoff, but it's very similar to the speech Sankin produces as an example of up-speak.

four score? and seven years ago? our f- I don't know if I'm getting this right. our fathers?

Here Sankin's pitch rises from 146Hz to 302Hz on score, from 147Hz to 288Hz on years ago, and from 135Hz to 274Hz on fathers. I'm not sure whether Sankin is intentionally using a rising intonation on the first example, but it has nearly the same degree of rise as her consciously produced example of up-speak. Its possible that she is affecting the pronunciation in both examples, but it may also be that she simply doesn't notice all examples of rising intonation – even when she produces them. (I'm sometimes mortified, but no longer surprised, when people point out my own use of the business neologisms I profess to dislike.)

But those are asides. My real issue with Gross and Sankin's discussion is its repeated moves to shame young women for producing “pet peeve” or “harmful” speech styles. Here is their discussion of up-speak.

Gross: Why does it drive you crazy when you hear up-speak?

Sankin: I think it makes women sound very immature, very unsure of themselves, and it's almost as if they're asking for approval. And I think that whole pattern is not helpful at all in terms of the way they present themselves, particularly in a professional environment.

Sankin also decries vocal fry (also known as creaky voice or glottalization) as harmful when produced by women.

Sankin: women are starting to imitate it and what they don't realize is how harmful it can be to your vocal chords.

[…]

Sankin: You sound very fatigued or bored or disinterested. It sounds like you don't have the energy to back up what you're saying.

(The other problems Sankin notes, “filler words” and her own pronunciation of the /o/ vowel, are not attributed to women but to young people and New Yorkers.)

As has been frequently noted, both by scholars and in popular media, these speech styles are not peculiar to women, but criticism of the styles focuses on women, especially young women.

Perhaps what made me notice the suggestion from Sankin, Gross, and Fresh Air that young women's voices may be pathological is its timing. This piece aired the same week as Nelson Flores' “What if we talked about monolingual White children…” and Deborah Cameron's “Just Don't Do It”. Both scholars offer an ironic story in which the speech of a privileged group (middle class English speakers in Flores' piece; business men in Cameron's) is described as pathological to illustrate and comment on the usual media discourses around women, young people, children of color, and other groups likewise seen as ‘problems’. Perhaps Fresh Air was a victim of poor timing as much as incomplete point of view. In any case, I'd recommend reading the latter bloggers, or the 2004 “text and commentaries” edition of Language and Woman's Place as an antidote to the women-and-youngsters-as-problem sections of the interview.

[Update 7/10/2015

Several people have pointed out that Fresh Air's decision to interview Thorpe and Sankin together, as well as some of the discussion of “sounding gay” positions gay men as pathological. See for example Sameer ud Dowla Khan's “open letter to Fresh Air with Terry Gross” on Facebook and KPCC radio's recent episode of Air Talk that featured Benjamin Munson.]

[Update 7/23/2015

On today's Fresh Air, Terry Gross interviewed Susan Sankin, linguist Penny Eckert, and journalist Jessica Grose on “policing young women's voices”. Audio and partial transcripts are available here.]

Oh, pants. January 21, 2016.

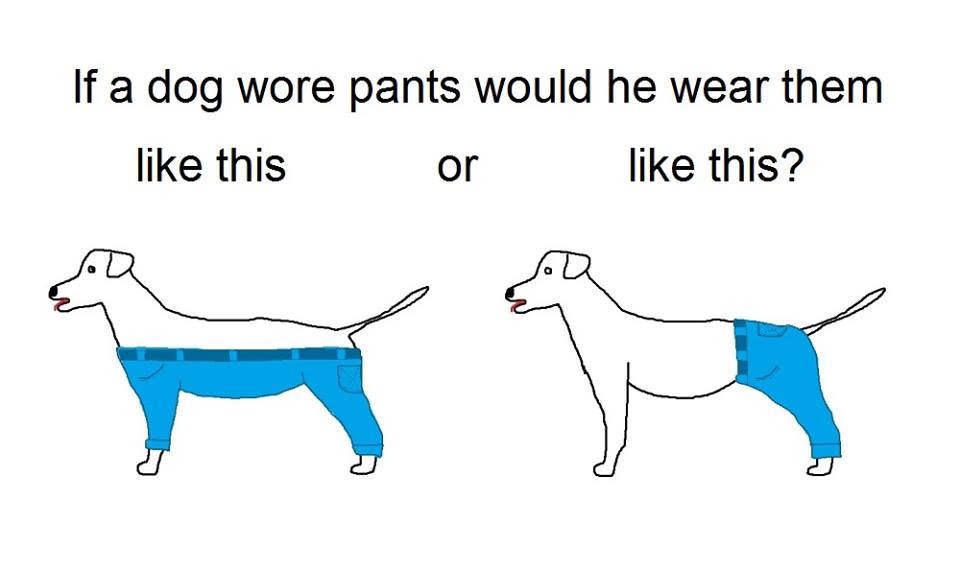

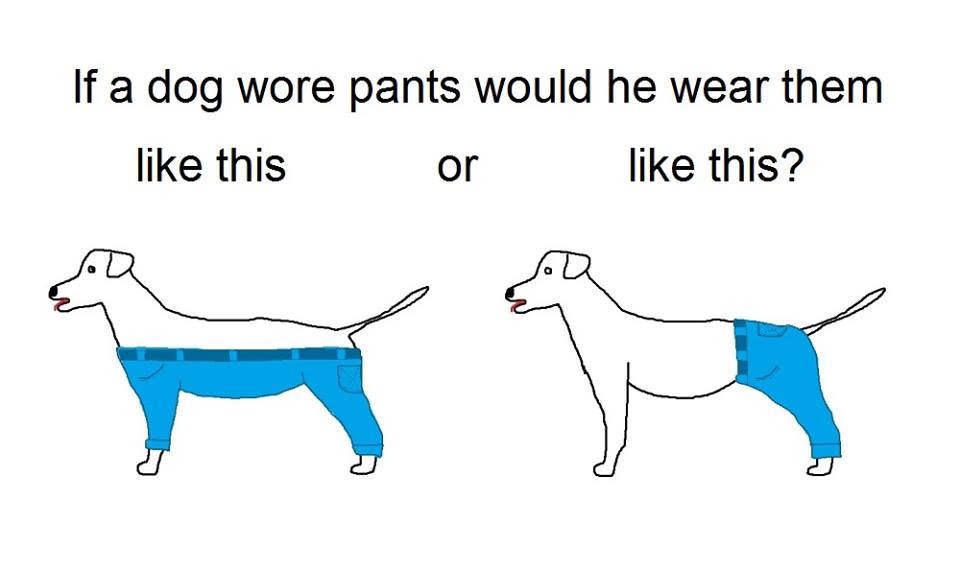

It all started (apparently) in the wee hours of the morning of 29 December 2015 with a doodle by a contributor at Utopian Raspberry – Modern Oasis Machine, a Facebook page specializing in “Memes I guess idk”. The artist wondered, in pictorial form, what ideal dog pants should look like: whether they should cover two legs or four.

The doodle that started it. Utopian Raspberry – Modern Oasis Machine, December 2015

From there, the drawing made its way to Twitter, Reddit, and other social media. Within a day or so it was being discussed in that other kind of media, including Maxim, New York magazine, and The Atlantic. (I would call that a meme, though idk with certainty.)

Robinson Meyer, writing at The Atlantic, argued for four-legged dog pants. Meyer reasoned, “Words mean things. […] pants cover all your legs. That’s what pants do. Humans wear two-legged pants because we have two legs. Dogs, on the other hand, have four legs. Ergo, dogs should wear four-legged pants. The left image is correct”.

And here is where the linguists come in. Jonathon Owen of the blog Arrant Pedantry noted in response to Meyer, “Even though it’s clear that words mean things, it’s a lot less clear what words mean and how we know what they mean.” Owen suggested ignoring dog pants temporarily in order to define what pants actually means. He suggested a definition of pants as garments that “cover your body from the waist down”. Based on that definition, “pants cover most or all of the pelvic area plus at least some of the legs.” Thus the four-legged version, which don't cover the dog's pelvis, don't fit the definition. Meyer's argument fails on its own terms.

Some supercilious commenter suggested that Owen would be better off employing prototype theory to “arrive at an understanding of bad pants and better pants.” Prototype theory, developed by psychologist Eleanor Rosch and employed by cognitive linguists such as Jean Aitchison and George Lakoff, suggests that meaning exists on a gradient. Rather than existing as logical definitions with necessary conditions, word meanings and other concepts are categories that can include prototypical and marginal members. To borrow Aitchison's example: the category BIRD contains “more ‘birdy’” types such as robins and sparrows, while ostriches and penguins are less birdy but still in the category.

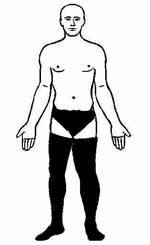

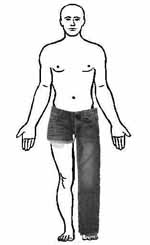

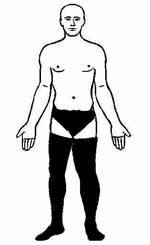

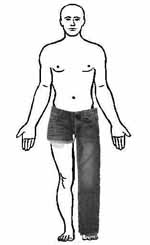

The supercilious commenter (me) undertook a small project by creating 10 images of a person wearing various things (or in one case, nothing at all) below the waist and asking 30 people whether the figure in each image was wearing pants. The results suggest that (contra Robinson Meyer) covering all your legs is neither necessary nor sufficient to a definition of pants. But to reference another meme, I think you'll find it's a bit more complicated than that.

Owen suggested that the four-legged dog pants resemble a backless jumpsuit, and that a jumpsuit is not pants. Most of my respondents agree with him; 19 people said a figure in a jumpsuit is not wearing pants. Nine people, however, said that the figure is wearing pants. (One respondent said “I don't know,” and one skipped the question.)

Most of the respondents (23 people) came from the United States. One came from Canada, one from the United Kingdom, and the rest from countries where English is not the majority language. That may help explain why 85% of them said that a figure wearing underpants and stockings was not wearing pants.

While the word often refers to underpants in the UK, in other English speaking areas, including the US, it refers to trousers. On the other hand, five people said that a figure wearing a bikini-style swim suit was wearing pants, though 23 (82%) said that he was not.

While the word often refers to underpants in the UK, in other English speaking areas, including the US, it refers to trousers. On the other hand, five people said that a figure wearing a bikini-style swim suit was wearing pants, though 23 (82%) said that he was not.

Nearly all respondents said that a nude figure (with genitals blurred but visible) was not wearing pants, though curiously the choice was not unanimous. One respondent said “yes”, the figure is wearing pants. Another illustration showed the figure in stockings with no underwear (genitals again visible). Although no one said this figure was wearing pants, one respondent said, “I don't know”.

To determine whether pants must cover all legs, the survey included three images of the figure wearing denim jeans. One pair of jeans was intact, covering both legs. One pair had both pant-legs cut off at the hips, and the third pair had one leg cut off and the other intact. Twenty five people (86% of respondents) said that the first figure, with both legs covered, was wearing pants. But the results were mixed for cutoff jeans: slightly fewer than half of respondents (41% for both legs cut; 48% for one leg) said cut jeans were pants, while more than half (59%) said the legless version were not pants. Only 37% said that the one-legged version shown here were not pants; 15% responded, “I don't know”.

To determine whether pants must cover all legs, the survey included three images of the figure wearing denim jeans. One pair of jeans was intact, covering both legs. One pair had both pant-legs cut off at the hips, and the third pair had one leg cut off and the other intact. Twenty five people (86% of respondents) said that the first figure, with both legs covered, was wearing pants. But the results were mixed for cutoff jeans: slightly fewer than half of respondents (41% for both legs cut; 48% for one leg) said cut jeans were pants, while more than half (59%) said the legless version were not pants. Only 37% said that the one-legged version shown here were not pants; 15% responded, “I don't know”.

So what have we learned? Well if nothing else we see that academics are just as willing as journalists are to tackle silly subjects during the holidays. But I think there are at least a couple of other conclusions we can make.

Most immediately, the survey suggests that pants don't necessarily “cover all your legs”. Some things that don't cover the legs are called pants, while some things that do cover the legs are not. The same is true of covering “the pelvic area plus”; no specific degree of coverage appears to constitute a necessary and sufficient definition of the English word pants.

More broadly, there doesn't seem to be any universally shared understanding of what pants refers to. Even the most pantsy images in the collection were not uncontroversial. Three people said that jeans are not pants, and one said that the figure shown here in trousers is not wearing pants.* Of course this is somewhat trivial. Individuals' understanding of the word's referent naturally may differ. Why should lexical knowledge be any less controversial than canine haberdashery? Yet it points to a less trivial notion as well.

More broadly, there doesn't seem to be any universally shared understanding of what pants refers to. Even the most pantsy images in the collection were not uncontroversial. Three people said that jeans are not pants, and one said that the figure shown here in trousers is not wearing pants.* Of course this is somewhat trivial. Individuals' understanding of the word's referent naturally may differ. Why should lexical knowledge be any less controversial than canine haberdashery? Yet it points to a less trivial notion as well.

There was not only disagreement across individuals, but uncertainty within an individual's understanding of the meaning of pants. Four respondents (15%) said “I don't know” whether a one-legged pair of jeans are pants. At least one respondent each gave that answer for the jumpsuit, jeans, stockings, or a kilt and sporran. Two people didn't know whether the nude figure was wearing pants.

Linguistic judgements are full of “gray zones” where native speakers lack certainty. This is true for semantic categories, syntactic judgements, phonological forms, social attitudes and ideologies, and a whole host of other areas. Analysts can force those judgements into binary categories, but should perhaps be skeptical of analyses that rely on such force.

*For each of the 10 images, the respondent was asked, “Is the figure wearing pants?” and allowed to select either “Yes”, “No”, or “I don't know”. It's therefore possible that the respondents were reacting to something other than the meaning of the word pants. However, the person who said “No” to dress trousers said “Yes” to all three jeans (whole, cutoff, and single-leg), while each of the three who said “No” to jeans said “Yes” to at least one other image.

Cuz it ain't in the dictionary. June 24, 2016

The title of this post is an allusion to a ditty I learned as a school boy, lo these many decades ago: “Ain't ain't a word 'cause it ain't in the dictionary.” The self-referential joke was always ridiculous on at least a couple of levels. At a basic level, the sentence uses ain't to declare the impermissiblity of using ain't. At a slightly more abstract level is the fact that inclusion in a dictionary does not bestow any special sense of wordhood. There is no dictionary induction ceremony. Dictionaries are, in general, attempts to describe the lexicon of a particular language. In rare cases the dictionaries of language planning authorities may prescribe words or spellings as standard, but except in the case of constructed languages dictionaries do not create the lexicon.

This morning in my English composition class, composed mainly of Japanese speakers, I came upon another pitfall of relying on “in the dictionary” as a test of acceptability. A student asked me whether a sentence that he wrote was correct:

I prefer urbanized areas to ruralized ones.

I told him that, although urban areas is perhaps better, urbanized areas is acceptable. On the other hand, ruralized areas is not. “Why?” he wondered. I explained that both urban and rural are useful adjectives to describe what I gather he had in mind. In addition, urbanize is a verb and the derived form urbanized can be used as an adjective. But since there is no verb ruralize, there is no derived adjective.

“But professor, ruralize is a verb. It's in my dictionary.”

Indeed it is – to my surprise. Obunsha Japanese-English Dictionary features the following (my translation):

ruralize, BRIT -ise /rúerəlàiz/

transitive. to make rustic [rural]

intransitive. to do rural activities

I had never heard this word. The Google Books n-gram viewer reveals that it is comparatively rare. While urbanize peaks at about 3 occurrences per million words in books published in 1975, ruralize hits a bit more than 1 per million in 1837 and is quite rare after about 1940.

The -ise spelling shows similar results. Peak ruralise hits in 1847 with 0.77 occurrences per million words and drops way off after 1946. In 1978 urbanise reaches about 0.51 per million words in the corpus.

The examples of ruralize or ruralise in Google Books appear to be mainly intransitive, meaning something like “go to the country” or pace Obunsha “do rural activities”.

The tourist who remembers the cottages of Argyle before fleets of steamers carried down the citizens of Glasgow to ruralize among its lochs and mountains, may estimate the wretchedness (“Scotch Topography and Statistics”, The Quarterly Review, 1848)

we wished to keep to ourselves, and that this company of motor ‘buses had been mainly formed in the interest of the working man, who desired to ruralise among us. (What the Judge Saw, Edward Abbott Parry, 1912)

I did spot this transitive usage, though I'm not sure I know what it means. Perhaps something like “carry out in a rural area”? “make appropriate to a rural area”?

There is a tendency at present for farmers' sons to be educated outside their own locality. To ruralise their education we must ruralise the curriculum of the Secondary Schools in provincial towns. (Papers by Command, House of Commons, 1918)

Google Books shows no occurrences of ruralise it or ruralize it, and only 325 ruralise/ruralize the in books published between 1800 and 2000, attesting to the obscurity of the transitive sense. (By way of comparison, the adjective rural appears in 225 books published in 1975 alone.) Several occurrences of transitive ruralize employ scare quotes. Perhaps the authors or their editors thought they were creating a nonce usage by analogy to urbanize.

The impulse to dress the park and ruralise the garden was irresistible, and the work of destruction was carried on with iconoclastic fury. (“Landscape Gardening”, The Quarterly Review, 1856)

But it is a mistake to suppose that any steps to ruralise the curriculum will appeal to the rural parent. (Progress of Education in India, 1923)

make those postings for a longer period, and move economists from the central banks to crop-research institutes — in short, ‘ruralise’ the public service. (Of Time and Place: Essays in Honour of O.H.K. Spate, 1980)

A more extensive and comparative treatment of the long history of failure of such attempts to make “relevant” and “ruralise” the school curriculum is provided by Foster and Sheffield (John Kurrien, Elementary Education in India, 1983)

And just to satisfy my sense of completeness: OED Online informs me that urbanize at one time meant “to make more refined or polished; to civilize, make urbane”. This sense is marked as obsolete, with the most recent example from Gentle Shepherd, an 1808 comedy by Allan Ramsay.

Lest they should shock good company by their honest open-hearted rusticity, shepherds have been brought to town by city poet after poet, and taught by their preceptors to act and speak with becoming delicacy. They have been introduced to new acquaintances; instructed in arts and sciences they never heard of before; and have been polished and urbanized by artificial refinements, till they have at last retained nothing either rural or natural, but, in some cases, their names.

There are two non-archaic senses of urbanize: “to accustom (a person) to life in a city or town”, and “to make urban in character or appearance”. It is from these senses that we derived the adjective urbanized.

While the word often refers to underpants in the UK, in other English speaking areas, including the US, it refers to trousers. On the other hand, five people said that a figure wearing a bikini-style swim suit was wearing pants, though 23 (82%) said that he was not.

While the word often refers to underpants in the UK, in other English speaking areas, including the US, it refers to trousers. On the other hand, five people said that a figure wearing a bikini-style swim suit was wearing pants, though 23 (82%) said that he was not. To determine whether pants must cover all legs, the survey included three images of the figure wearing denim jeans. One pair of jeans was intact, covering both legs. One pair had both pant-legs cut off at the hips, and the third pair had one leg cut off and the other intact. Twenty five people (86% of respondents) said that the first figure, with both legs covered, was wearing pants. But the results were mixed for cutoff jeans: slightly fewer than half of respondents (41% for both legs cut; 48% for one leg) said cut jeans were pants, while more than half (59%) said the legless version were not pants. Only 37% said that the one-legged version shown here were not pants; 15% responded, “I don't know”.